In Conversation with Tony Albert

In Conversation with Tony Albert

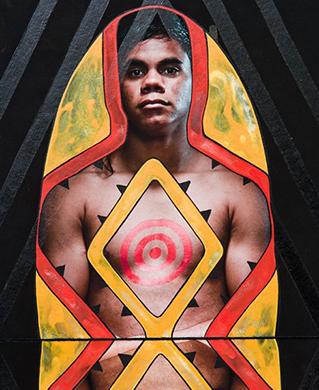

Image 1: Brothers (detail). Courtesy and © Tony Albert, 2013.

Image 1: Brothers (detail). Courtesy and © Tony Albert, 2013. Image 2: Brothers (detail). Courtesy and © Tony Albert, 2013.

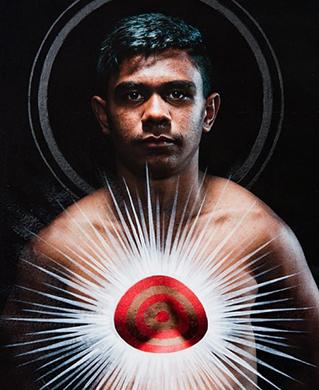

Image 2: Brothers (detail). Courtesy and © Tony Albert, 2013. Image 3: Brothers (detail). Courtesy and © Tony Albert, 2013.

Image 3: Brothers (detail). Courtesy and © Tony Albert, 2013. Image 4: Brother (Our Present) detail. Courtesy and © Tony Albert, 2013.

Image 4: Brother (Our Present) detail. Courtesy and © Tony Albert, 2013.

In Conversation with Tony Albert | By Suzanne Buljan

Visiting Tony Albert recently in his studio, on a very hot steamy day was a special treat. Immersed in collections, the making of work and ideas, I felt inspired and the robust conversation that followed was the cherry on the cake.

A few questions for Tony:

SB: I am particularly interested in how artists are engaging with social media to support their practice. How do you utilize social media?

TA: Social media is important. It is an extension of the work. Your profile is easily accessible online and people from outside your realm comment and engage. The comments are important, and provide a good sense of the Australian public thoughts and mood. It is about the here and now.

In a sense, you are no longer the mysterious artist – by employing social media, your practice is very much in the public space. I’m very mindful of the bubble I live in. I am a minority in the bigger scheme of things. Social media can access people you wouldn’t necessarily in day-to-day living. My friends and colleagues are all quite similar and have similar beliefs regarding their environment and politics. I’m quite left. But outside that bubble is a world of possibilities and opinions.

Twenty years ago there was no access point for artists. Now, the audience has one…as an artist putting their work out there, social media is incredible at filtering the audience.

I use instagram, facebook and I’m working on my own website. It was something I never considered in the past, but now it’s essential.

SB: Is this period a tipping point for artists (especially photomedia) and their use of traditional processes? We’re living in this digital age yet we still feel drawn to the artifact, the tactile.

TA: It’s funny, we don’t know how far behind we are. I say it has to be material, yet I understand the future may be paperless.

SB: What is it about materiality and the ‘document’?

TA: We are somehow unaware of the implications and I know in my heart we have to stop using paper, but the physicality of holding onto something in our hands is so appealing. Language itself it changing and as I listen to my nieces and nephews, they’re dialogue is so interesting and ‘new’. Technology is everywhere, in school and at home and they are so much more aware.

SB: So if Gen Y is political and very aware…is there hope in future generations?

TA: Yes, of course there is hope.

SB: You were Richard Bell’s studio assistant for a period and you’ve just moved studio. How important is the physicality of a studio to your work?

TA: I need a space I can come to, and get away from. But I always like people in the space. It creates dialogue. To me its super important, a studio is a creative hub. I refer to it as a cyclone of energy. The difference in making work is apparent, as we don’t hide what we are doing. By putting together ideas, books, movies, etc…it’s really an extension of my family upbringing. Whether it’s for humor or for a laugh, or the exchange of ideas, its important for me.

SB: Is this our true nature when not online?

TA: Its funny, there is so much conversation about social media at the moment. There is a danger in not physically interacting with people, but if we stay true to our nature as social beings it can be used responsibly.

SB: People are becoming more and more ‘glued’ to their screens. Do you think ‘conversation’ is being replaced with text.

TA: People are saying LOL now instead of ‘laughing’…we’re going to have a new language.

SB: Bell has described himself as “an activist masquerading as an artist.” Your work examines body politics and identity – How is photography a mediating device for you?

TA: It’s looking at myself in the conceptual realm as an artist. I’m not comfortable with the term photographer. I engage creative people that I feel comfortable working with. Like when making Brothers in 2012. Using the immediacy of photography when capturing the Brothers, I needed young men taking their shirts off to be beautifully shot with no distraction. It’s a staged documentation of a real event. They needed to be in your face with a target on their chest. It allows me to tell truths through representation.

SB: What is unique about the representational language of photography for you, as opposed to other aesthetic systems?

TA: It has to be based on something about capturing that immediate image. Why did I pick photos? Real people in real photos are the best representation of what I was examining at the time.

SB: What if I said photographs are really a construction and not documentation? By choosing a subject and framing a shot you as the photographer are constructing a reality. Playing devils advocate here.

TA: Mervyn Bishop took a photo of Vincent Lingiari and Gough Whitlam in 1975. The ceremony took place in a tent and it was in shadow, so they re-shot the photo outside. For most people it’s a total reproduction, you can re-create and re-enact things and it can still be perceived as the actual event at that time.

In 1966, Aboriginal stockmen went on strike at Wave Hill station in the Northern Territory. Under the leadership of a Gurindji man, Vincent Lingiari, the strikers set up camp at Wattie Creek. Over time, the industrial dispute with the Vestey family turned into a demand for land rights. Nine years later, in 1975, the Whitlam Government resolved the dispute and title to the land was granted to the Gurindji people. During the ceremony to grant the land title, Whitlam symbolically poured sand into Lingiari’s hand.

SB: Speaking of place, are your immediate surroundings integral to your work? Do the places you interact with inform your work etc?

TA: For me as an artist, place is much stronger than what I am doing. I am surrounded by my physical collection and I am affected by the events around me. Brothers, was inspired by an event that took place in Sydney’s Kings Cross in 2012 whilst I was in residence at Art Space in nearby Woolloomooloo. Some teenage boys were joyriding and injured a pedestrian when they lost control of their car. Police shot and wounded two of the boys in an effort to defuse the situation. As young Aboriginal men they were most likely targeted – this is why I’ve put the large targets on the chests of the teenagers in this work.

SB: Are you interested in documents or artifacts?

TA: It’s more the latter. I collect ‘Aboriginalia’ as part of my practice. Museums should be collecting these objects. There was a generation of people who grew up with this psyche and actively collected anything with an Aboriginal on it, yet it is swept under the carpet in some kind of PC embarrassment. It’s profound. I guarantee that nearly every collectible object has had an Aboriginal face printed on it.

SB: Premise for a show?

TA: Not yet. I am more interested in what they have. I know things immediately and I am more interested in the fact that it exists than just working on it.

SB: How do we as a society show archives or collections that contain Aboriginal heritage? How would you show it in a contemporary sense?

TA: The question is – why did society do this in the first place, and then store it in a box… archived. Interrogating this question is the answer.

SB: And as for the community?

TA: I love this idea. To have the Aboriginal community who are not artists, hold onto the information and make it safe. It requires the collectors to have trust and talk about those things and at the end of the day, hand it over.

SB: Your works shift effortlessly between various media. Do you have a favourite?

TA: My collection is my favourite thing.

SB: If photography pretends to show reality, are you capturing ‘realities’ in your images or creating pictures?

TA: It’s definitely a reality. Walking around as breathing targets (Aboriginal men) but then with other photographic work where I have men wearing masks. It was about creating a character or a metaphor. With the Brothers work, I would see it as documentation, but it’s metaphorical. For instance; a young boy was on a chair where he had a mark on his chest…he was a living, breathing target.

SB: Do you consider this prejudice a particularly Australian phenomenon?

TA: No, it’s far more of a global concern than a community based issue. In nearly every image of brutality I have come across, the victims were of colour, or of a minority group.

SB: Is Australia ‘multicultural’?

TA: Australian multiculturalism sees people of different cultural or racial backgrounds living in close proximity as multicultural, but real multiculturalism is living together in harmony.

SB: What of the current political climate in Australia?

TA: I am witnessing the worst politics in my young life. We’re getting more conservative. Does your socio-economic background make a difference? Does being a man or a woman make a difference? Does colour make a difference?

SB: Back to activism?

TA: Look at my work. When people, especially Aboriginal people write about my work, they still have a colonial mind, it’s crazy. I would really love someone who is objective to write about my work. Awareness is one thing, but making informed choices are more important.

SB: How political can you be as an artist?

TA: It can be in your work and it can be how you manage your work. I am at a point where I can say ‘no’ to a show if I don’t like what is going on. It’s about education. Things I am involved in mean something.

SB: You now have a voice, where as others don’t. Why art in the broader sense?

TA: There is a point where art is the vessel. Without that, it’s the engagement. Everyone is an artist. If you don’t have that voice, you can’t conjure it, and you institute walls. In reality, the work you hate the most, you have to empower to love the most. Art can be more than just a pretty picture… often it’s not a bad thing.

SB: What or who is your muse?

TA: It’s my family, it’s my culture…it’s my life. Gary Foley recently opened an event in Victoria and said something along the lines of, “I don’t know much about the art of history, but I know the history of art”. This resonated with me. Even though I have a degree in Indigenous art, I’m not researching anything that is foreign to me. If you like football, then make work about football.

SB: Where to next?

TA: I love this studio, with all my things, but we have to be out in December. I will be in New York for six months – the ISCP studio program. I love New York, it’s my favourite place in the world.

SB: You must read Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York. It’s a history of diversity.

TA: The diversity of people in New York is really not America. In New York, you walk past 10 people and they are completely different, but it is a bubble. It’s not like any other place in America.

SB: Keep in touch.

Tony is represented by Sullivan + Strumpf